Fallacy is the use of faulty reasoning which results in an unsound argument. Fallacy may have been committed intentionally to manipulate the audience, or unintentionally due to carelessness or ignorance. Critical audience often points out fallacies or flaws in an argument. Knowledge of logical fallacies will help you to build a fallacy-proof argument, hence stronger credibility.

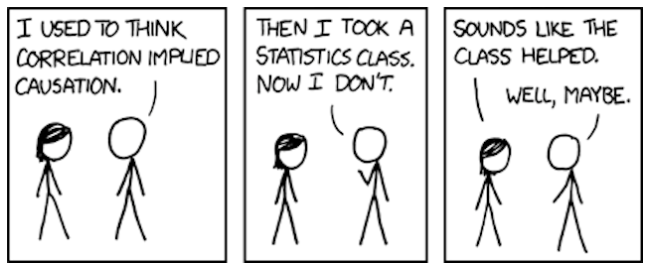

1. Correlation does not imply causation

Also known as cum hoc ergo propter hoc, Latin for “with this, therefore because of this”, or false cause. When two findings, A and B, are found to be correlated, it is tempting to conclude that A causes B (direct causation) or that B causes A (reverse causation) despite there are other possibilities to explain the relationship between A and B:

- A causes C which causes B (indirect causation)

- A and B are consequences of a common cause, but do not cause each other

- A and B are coincidence

Further investigation is required to determine the cause-and-effect relationship between A and B.

Example:

“The falling revenues that the company is experiencing coincide with delays in manufacturing. These delays, in turn, are due in large part to poor planning in purchasing metals. Consider further that the manager of the department that handles purchasing of raw materials has an excellent background in general business, psychology, and sociology, but knows little about the properties of metals. The company should, therefore, move the purchasing manager to the sales department and bring in a scientist from the research division to be manager of the purchasing department.”

Analysis:

The author fails to establish a causal link between falling revenues and delays in manufacturing. Correlation is not sufficient to establish that the cause of falling revenues is the delays in manufacturing.

2. Hasty generalisation

When an event X is true for S, subset of population P, it is tempting to conclude that X must be true for the whole population P. It is unreasonable to draw a universal conclusion for the whole population based on a small subset.

The reverse is also a fallacy in which we cannot draw a definite conclusion for a subset S since the conclusion is applicable for population P as a whole.

Example:

“There is a common misconception that university hospitals are better than community or private hospitals. This notion is unfounded, however: the university hospitals in our region employ 15 percent fewer doctors, have a 20 percent lower success rate in treating patients, make far less overall profit, and pay their medical staff considerably less than do private hospitals. Furthermore, many doctors at university hospitals typically divide their time among teaching, conducting research, and treating patients. From this it seems clear that the quality of care at university hospitals is lower than that at other kinds of hospitals.”

Analysis:

We cannot debunk a universal conclusion that university hospitals are better than community or private hospitals with just hospitals in a region as they are not representative of all hospitals. More evidences are necessary in order to debunk the common notion.

3. Ambiguity

In this fallacy, a claim is made based on an ambiguous interpretation of a term.

Example:

“Writers who want to succeed should try to write film screenplays rather than books, since the average film tends to make greater profits than does even a best-selling book. It is true that some books are also made into films. However, our nation’s film producers are more likely to produce movies based on original screenplays than to produce films based on books, because in recent years the films that have sold the most tickets have usually been based on original screenplays.”

Analysis:

The author equates “success” with “profits” while there are many definitionx of success such as number of awards, positive critical receptions, or personal rewards.

4. Texas sharpshooter

To commit this fallacy, a universal conclusion is derived from cherrypicked sample which seems to favour the conclusion.

Example:

“The common notion that workers are generally apathetic about management issues is false, or at least outdated: a recently published survey indicates that 79 percent of the nearly 1,200 workers who responded to survey questionnaires expressed a high level of interest in the topics of corporate restructuring and redesign of benefits programs.”

Analysis:

We cannot determine for sure that workers are generally apathetic is false since most likely only workers who are not apathy are willing to respond to the survey questionnaires. Hence, the survey result is not representative of all workers’ view towards management issues.

5. False dilemma

Also known as black and white or either/or. False dilemma is committed due to mistaken reasoning that there are only two choices exist, failing to take into account other possible choices.

Example:

“Re-elect Adams, and you will be voting for proven leadership in improving the state’s economy. Over the past year alone, seventy percent of the state’s workers have had increases in their wages, five thousand new jobs have been created, and six corporations have located their headquarters here. Most of the respondents in a recent poll said they believed that the economy is likely to continue to improve if Adams is reelected. Adams’s opponent, Zebulon, would lead our state in the wrong direction, because Zebulon disagrees with many of Adams’s economic policies.”

Analysis:

The author urges the audience to either vote for Adam, for better economy, or Zebulon, for worse. The author fails to take into account that Zebulon’s economic policies could be in fact improve the state’s economy even better than Adam.

Note: the argument used to explain the fallacies below is taken from GMAT AWA list of topics.